Always A Good Idea To Start A New Year Thinking About Dostoevsky, Right?

- Howie Klein

- Jan 1, 2022

- 7 min read

I bet Cathy Young spent a lot more time writing her essay, Dostoevsky at 200: An Idea of Evil, than most writers spend on their pieces for Bulwark... and I wouldn't be surprised if far fewer people read it than other pieces looked at by people casually browsing the conservative anti-Trump publication. Being a big fan of Dostoevsky's books, I was happy to learn I was in good company when I read that Figures as diverse as Sigmund Freud, Jean-Paul Sartre [and Ayn Rand-- ugghhh] "admired his genius while vehemently rejecting his beliefs, and even detractors such as Nabokov could not quite escape his magnetism."

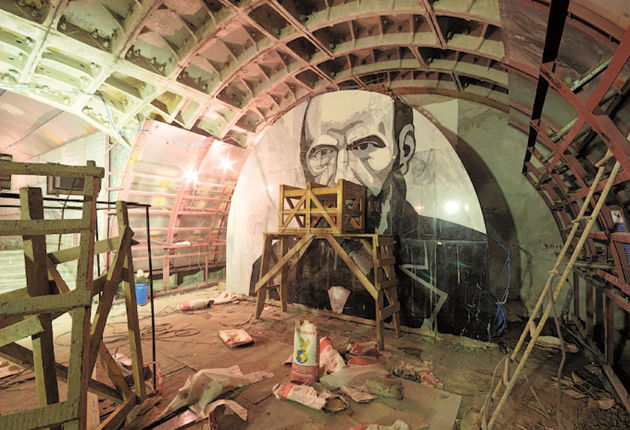

When I visited Moscow with two friends in 2016-- all of us intrepid travellers-- we did something very out of character for our style of traveller. We hired a guide to help us navigate such a difficult and foreign metropolis-- and she took us to see a cemetery and for a tour of metro stations. My favorite writer is buried in St Petersburg-- so I had to satisfy myself by visiting the graves of Chekhov, Gogol, Prokofiev, Stanislavski and Nikita Khrushchev-- but a relatively new metro station had been dedicated to him a few years earlier, the Dostoevskaya metro station, whose decor-- scenes of violence from Dostoevsky novels-- had caused, our guide told us, some controversy. Dostoevsky? Controversy? Imagine that!

Not just his work, but Doestoevsky's entire life was... controversial. Young wrote that Dostoevsky's "titanic stature rests on four novels written after his 1855 return from the penal colony: Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868-1869), The Demons, a.k.a. The Possessed (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880); one could also add to this list the 1864 proto-existentialist novella Notes from the Underground."

In the 2004 book How Russia Shaped the Modern World, Clemson University historian Steven G. Marks describes Dostoevsky’s contribution as “messianic irrationalism.” Obviously, literature had dealt with the irrational before Dostoevsky, but he delves into the subterranean elements of the human psyche with a new, terrifying and riveting intensity, exploring obsession, guilt, self-loathing, love/hate attachments, paranoia, and self-destructiveness. The “man from the underground” rejects rationality as a matter of principle, rebelling against the necessity of accepting that 2+2=4. In The Demons, the brilliant and tormented Nikolai Stavrogin, a sort of Byronic antihero on speed, does terrible things (among them, as revealed in an initially censored chapter, the rape of a child) in a desperate challenge to God and to his own conscience, as well as an attempt to fill his inner emptiness. The most famous Dostoevsky protagonist, Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, sets out to kill an old pawnbroker to validate his theory that a superior individual can sacrifice others to his goals unbound by guilt or morality, then spends the rest of the story in a feverish struggle with the burden of his act.

In all these works, the line between irrationality and insanity is thin and often blurred. (Interestingly, Dostoevsky explicitly disavows such an interpretation in Stavrogin’s case-- the novel’s final line states that after his suicide, the medics at the inquest “categorically and adamantly ruled out insanity”-- but the reader may beg to differ.) The French writer and critic Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé, one of Dostoevsky’s biggest champions in Europe in the late nineteenth century, nonetheless dubbed him the “Shakespeare of the lunatic asylum” and noted that every one of his characters was a potential case for the neurologist Jean Charcot. Nabokov was much more scathing; in his Dostoevsky segment of Lectures on Russian Literature, he scoffs that one can hardly speak of “realism” or “human experience” when discussing “an author whose gallery of characters consists almost exclusively of neurotics and lunatics.”

...[O]ne of Dostoevsky’s literary triumphs is that he manages to make ideas gripping. In Crime and Punishment, the focus of suspense is at least as much on Raskolnikov grappling with challenges to his theory, which separates superior individuals from “trembling creatures,” as on whether he will get caught. In The Brothers Karamazov, the debates about faith, freedom, human suffering, the moral balance of the universe, and whether “everything is permitted” in the absence of God are as fascinating as the family drama and the murder mystery (with which these debates are deeply intertwined). The conversation between the devout Christian Alyosha and the skeptic Ivan about God, suffering, freedom and evil—which includes the justly famous “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor,” Ivan’s tale about a medieval Spanish cardinal who witnesses the return of Jesus and promptly throws him in the dungeon-- may well be the pinnacle of philosophical literature.

The ideas have also made Dostoevsky perennially controversial. A socialist early in his career, he came out of the penal colony a conservative Christian. The Demons, his most political work-- conceived as a “pamphlet-novel” and fictionalizing an actual incident in which a man who tried to leave an underground revolutionary group was murdered by his former comrades-- has been rightly hailed as a brilliant, terrifyingly prophetic portrayal of Russian revolutionary radicalism. (In their new book Minds Wide Shut: How the New Fundamentalisms Divide Us, Northwestern University scholars Gary Saul Morson and Morton Schapiro write that The Demons was “the only nineteenth-century work to have foreseen what we have come to call ‘totalitarianism.’”) Yet the book’s targets also include pro-Western liberals, depicted as well-meaning but foolish accomplices to the radical destroyers. Shatov, the doomed ex-revolutionary who sees the light, is often assumed to channel the author’s own views in a speech articulating a militant religious nationalism: Society can only be founded on faith, with reason and science relegated to a subordinate role; national identity is irrevocably connected to nation’s “own special God,” and a nation can be great only “for as long as it believes that it will prevail with its God and banish all the other gods from the world”; in the end there is only one true God, and the Russian people is the only “God-bearing people.”

It’s not entirely clear, in fact, that Shatov is fully a vehicle for Dostoevsky himself. (Right after the reference to the “God-bearing people,” he breaks off and declares that he knows his words could be either “old, worn-out rubbish, grist for every Slavophile mill in Moscow, or a completely new word, the last word, the only word of resurrection and renewal”; it is also worth noting that his religious-nationalist zeal has been instigated by Stavrogin in a deliberate experiment.) But there is little question that Dostoevsky saw Russia as having a special mission-- though, unlike “true” Slavophiles, he believed it should incorporate Western cultural influences-- and that Christianity, for him, was at the heart of this mission. To Dostoevsky, the West was mired in godless liberalism and materialism, and it was Russia’s role to save it by bringing it back to spirit of Christ.

This message may seem especially relevant today when the revolt against liberalism, from both the left and the right, is an increasingly popular stance in the West itself while nationalism and populism are ascendant. Dostoevsky’s critique of Western secularism and consumerism, and what Shatov calls “half-science,” “humanity’s most terrible scourge”-- probably something akin to what we now call “scientism”-- will no doubt strike many social and religious conservatives as startlingly prescient. (They may be chagrined to learn that he regarded Roman Catholicism as the beginning of Europe’s loss of true Christianity and believed that even atheism was preferable-- though that didn’t stop him from having a profound appeal for such Catholic thinkers as Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy.)

Doestoevsky's linkage of religion, nationalism, and populism can also sometimes seem to approach the “national conservatism” advocated in recent years by American-born Israeli political scientist Yoram Hazony. But therein lies a cautionary tale: Dostoevsky’s religious nationalism has a very marked dark side. In 1876-77, it led him to agitate for the Russo-Turkish war, which he believed could unify the people in a sacred endeavor-- helping fellow Slavs and Orthodox Christians oppressed by the Ottoman Empire-- and to urge the conquest of Constantinople. It also expressed itself, on many occasions, in virulent hostility toward “alien” groups that didn’t fit his vision of a godly Russia united by Orthodox Christianity: Catholic Poles and, notably, Jews.

...It’s not surprising to learn that, as Marks notes in How Russia Shaped the Modern World, Dostoevsky inspired some far-right intellectuals in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s who saw him as the mortal enemy of decadent liberalism. Equally unsurprising is the fact that today, he is being embraced by Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia. In an essay on Dostoevsky’s 200th anniversary in the online magazine Sobesednik (“Interlocutor”), the eminent writer and critic Dmitry Bykov suggests that Dostoevsky should be “scrubbed clean of [the regime’s] sticky love, which can only compromise the writer and the thinker”; but he also notes that in a sense, Dostoevsky is “the father of Russian fascism.”

Of course, as Bykov acknowledges, Dostoevsky is also much more than that. For one thing, he is too independent and too paradoxical to be a propaganda tool. His cultural conservatism was idiosyncratic enough to coexist with strong sympathy for Russia’s nascent feminist movement. His support for tsarist Russia’s symbiosis of church and autocracy-- a stance Bykov regards as a “Stockholm syndrome” response to Dostoevsky’s pardon by the tsar in 1849-- inevitably clashed with his passion for human freedom, which is the central theme of “The Grand Inquisitor”: The Inquisitor sees Jesus as a carrier of dangerous heresy for giving people free choice rather than the safety of authority. As Russian religious philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev argued more than half a century after Dostoevsky’s death, Dostoevsky himself may not have understood that, despite its Catholic setting, his story applied equally to Russian Orthodoxy: “In actuality, Dostoevsky in the Legend rose up against every religion of authority, as being a temptation by the Anti-Christ... This was an unprecedented hymn to the freedom of the Spirit, a most extreme form of religious anarchism.” It is not for nothing that in the 1890s, Russian censors barred The Brothers Karamazov from school libraries and free public libraries as insufficiently, well, orthodox.

Bykov believes that toward the end of his life, Dostoevsky’s views were evolving again: There are tantalizing hints that the planned second volume of The Brothers Karamazov was going to take the saintly Alyosha in the direction of becoming a revolutionary. It is also worth noting that in the acclaimed speech Dostoevsky gave in June 1880-- just six months before his death-- at the unveiling of the monument in Moscow to Russia’s great poet Alexander Pushkin, he strove to articulate a Russian patriotism that would reconcile the Slavophiles and the Westernizers, emphasizing Pushkin’s Europeanness and “pan-humanity” as an essential part of his Russianness.

Perhaps no Russian writer attained this “pan-humanity” more than Dostoevsky, who has, for a century and a half, inspired people across national, religious and political lines-- including members of groups toward which he harbored the strongest prejudices. This is one way in which Dostoevsky’s legacy is relevant to our cultural moment: It is a reminder that great art and literature transcend their creators’ politics and biases and endure long after the polemics of the day are forgotten.

The most glaring difference between him then and us now is... at least he thought about his inner contradictions. Or he pretended to. It's hard to tell.

I do know that almost nobody engages in introspection any more. No matter how evil your impulse is, you can find a multitude of others to support you.

No matter how stupid you are, there are hordes who are more stupid. And society does not seem to care.

"...the moral balance of the universe, and whether “everything is permitted” in the absence of God..."

No such introspection required any more, or ever, really. Christians have not just excused but sanctified their misanthropic impulses as godly since the writers of the old testament starte…