MAGA: Bad For The Jews

- Howie Klein

- Feb 21, 2024

- 6 min read

In 2020, virtually all the Hasidics who voted, or at least all the Hasidics in Brooklyn who voted, cast their ballots for Señor Trumpanzee. Hasidics notoriously absolutely vote as a bloc... and it's their rabbis who make the call. But overall, according to the most reliable exit polls, around a third of Jewish voters say they cast those 2020 presidential ballots for Trump.

I was talking with a friend the other day about the importance of Grover Cleveland to American Jews. My friend quickly became obsessed with this Reagan thing he found online and I was talking to him about the anti-Semitic immigration law Republicans in Congress passed and Cleveland, a Democrat, vetoed. Hasidics aside, Jews are supposed to be very well educated... so what's this voting for Republicans thing for one in three? I mean one in three-hundred I could understand but... one in three?

These Jewish Trump supporters may be in for a surprise if Trump managers to get back into the White House. Alexander Ward and Heidi Przybyla wrote that one of the Trumpist think tanks— led by heavy duty Trump personality, Russell Vought, director of the Office of Management and Budget during his first term and a potential chief of staff in the next one— is developing plans to infuse Christian nationalist ideas in his administration. “Christian nationalists in America” they wrote, “believe that the country was founded as a Christian nation and that Christian values should be prioritized throughout government and public life. As the country has become less religious and more diverse, Vought has embraced the idea that Christians are under assault and has spoken of policies he might pursue in response.”

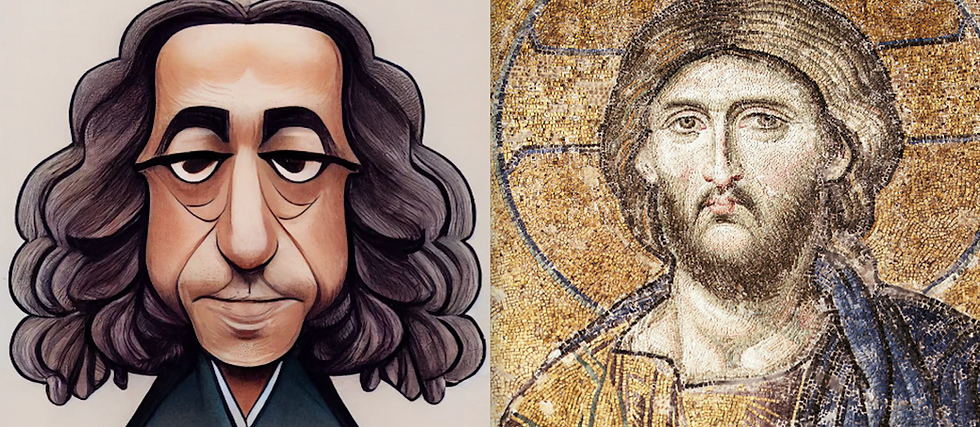

If you ask any of the AI platforms to name the most significant Jewish philosophers— excluding Moses and Jesus— they all rank Baruch Spinoza in the top three (Maimonides always ranking numero uno) and cite his 17th century masterpiece, The Ethics, which presents a systematic account of reality based on the principles of reason and determinism, as crucial. Often called an atheist, he challenged the divine origin of the Old Testament and the power wielded by religious authorities. Having been expelled from Amsterdam by the Jewish authorities, he died at 44 in The Hague (1677). The Catholic Church banned his posthumous works.

Ian Buruma, author of Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah introduced many NY Times readers to him yesterday as a bulwark against the narrow-mindedness of MAGA-ism. Buruma wrote that the great and outspoken philosopher and defender of freedom “suffered much for his lifelong dedication to the freedom of thought and expression. His view that God did not create the world, and his disbelief in miracles and the immortality of the soul so enraged the rabbis of his Sephardic synagogue in Amsterdam that he was banished from the Jewish community for life at the age of 23. Only one of his books, about the French philosopher Descartes, could be published under his own name during his lifetime. His other works, arguing against religious superstition and clerical authority, and for intellectual and political liberty, were considered so inflammatory that his authorship had to be disguised... Living now as we do in a time of book-banning, intellectual intolerance, religious bigotry and populist demagoguery, his radical advocacy of freedom still seems fresh and urgent... Spinoza’s idea that God was not a thinking or creative being but nature itself was considered so scandalous that George Eliot, the British novelist who translated Spinoza’s Ethics in the 1850s, still insisted that her name not be mentioned in connection with the thinker she unreservedly admired.”

Spinoza was convinced that all people, regardless of their religious or cultural background, were imbued with the capacity to reason and that we should seek the truth about ourselves and the world we live in. He insisted that our rational faculties could provide us with not only more precise knowledge, but with a path toward a happier life and better politics. In an essay called “On the Correction of the Understanding,” he wrote: “True philosophy is the discovery of the ‘true good’, and without knowledge of the true good human happiness is impossible.” That true good, in Spinoza’s view, can only be found through reason and not through religion, tribal feelings or authoritarianism.

Unlike Thomas Hobbes, who believed that only an absolute monarch could keep man’s violent impulses in check, Spinoza was an early proponent of a democratic ideal and representative government. But a free republic could only survive under a government of reasonable men who knew how to cope with conflicting interests rationally. As Spinoza put it, perhaps a little too optimistically, in his “Theological-Political Treatise”: “To look out for their own interests and retain their sovereignty, it is incumbent on them most of all to consult the common good, and to direct everything according to the dictate of reason.”

…The greatest enemies of his kind of truth-seeking in Spinoza’s time were the orthodox Calvinists who still dominated academic and religious life— and to some extent politics— in the Dutch Republic. Catholics in France, strict Anglicans in England, and the rabbis who expelled him, were no different. Their idea of truth was revealed in the Holy Bible by God’s words. They saw Spinoza’s philosophy as a direct challenge to their authority. And so, his blasphemous insistence on rational thinking, and the freedom to challenge religious dogma, had to be crushed.

Religious dogma is often still used today to crack down on the free thought. This is the case in Muslim theocracies, such as Iran. But it is true also of evangelical Christians in the United States, who insist on the removal of books in public libraries and schools that supposedly offend their moral beliefs grounded in religion.

Dogmatic oppression of intellectual freedom need not always be religious, however. Chinese citizens cannot express themselves freely, as long as the government insists that all views conform to party ideology. As with religious ideologues, they like to claim that dissident ideas “offend the feelings of the people.”

In the United States, and increasingly in many parts of Europe, other kinds of ideological thinking, some of them with commendable social goals, such as social or racial justice, put pressure on intellectual freedom as well. Spinoza’s insistence on the primacy of our capacity to reason would not sit well with the notion that our thoughts are driven by collective identities and historical traumas. He was against tribalism of any kind. And he would not have considered offended communal feelings as a rational argument.

Spinoza is sometimes dismissed as a rationalist, who had no understanding of human emotions, but he knew perfectly well that we are feeling human beings, and that emotions can get the better of us. One of his greatest fears, no less germane today than in his time, was that mobs, whipped up by malevolent leaders, would squash free thinking with violence.

The way to deal with religious beliefs and human emotions, in Spinoza’s opinion, was not to try and ban them, or pretend they didn’t exist. Let people believe what they want, as long as philosophers could enjoy the freedom to think. In his ideal republic, there would be a kind of civic religion, beyond the authority of clerics, that would improve and safeguard moral behavior. In his own words: “The worship of God and obedience to him consists only in Justice and Loving-Kindness, or in love toward one’s neighbor.”

In the universities, too, Spinoza did not think that the religious approach to truth could be abolished. The answer was to separate religious knowledge from science. There was room for both, without one encroaching on the turf of the other.

In our own time, we see demagogues inciting the masses with irrational and hateful fantasies. We see universities torn by ideological struggles that make free inquiry increasingly difficult. Once again there is a conflict between the scientific and the ideological approaches to truth. For example, the notion in some progressive circles that the teaching of mathematics is a form of toxic white supremacy and must be pressed into the service of correcting racial injustices, is, as some people might put it, problematic.

This certainly would have puzzled Spinoza, but he might have helped us find a way out. We could follow his example of distinguishing between different ways to find the truth. It is true that racial and other social injustices persist and should be corrected, but the logic of mathematics is universal and must not be compromised to further the interests of particular minorities. Scientific inquiry should be culturally and racially neutral.

The freedom to act and think rationally, not dogmatically, is by far Spinoza’s greatest legacy. It is the only way to combat the threat of irrational ideas, stirred up hatreds and the confusion of science and faith. And it may be the only way to save our Republic.

If you don't want the words of Spinoza to be applied to everyone, including your audience, you shouldn't have quoted him.