Fascists Always Glorify, Even Celebrate, Violence-- And That Includes The Trumpist GOP

- Howie Klein

- Nov 11, 2021

- 14 min read

The Republican Party no longer stands for much outside of unquestioning obeisance to their Dear Leader. That and right-wing cancel culture-- from book banning and burnings to denialism as part of school curricula. A poll released Wednesday by Monmouth shows that although most Americans (75%) agree that public schools should be teaching about the history of racism-- and only 21% disagree-- among Republican voters, 43% oppose teaching about historical racism. That'll make it disappear!

Meanwhile, NBC reported today that domestic extremists have continued pushing violence against Congress and school and health officials. I'm sure the judiciary's and the DOJ's refusal to treat this seriously in going to make it much worse-- which is why I have endorsed forcing Merrick Garland to retire. This morning NBC News' Ken Dilanian reported that "Domestic extremists continue to exploit false narratives to promote violence online, calling for attacks on members of Congress and public health and school officials, even as they share information about how to build bombs, according to a new intelligence bulletin by the Department of Homeland Security that paints a picture of persistent danger."

These are dangerous, even murderous, criminal elements who are being encouraged and coddled by insurrectionists like, from left to right: Marjorie Traitor Greene (pictured here trying to catch and eat a fly), Ted Cruz, Matt Gaetz, Lauren Boebert, Madison Cawthorn, Josh Hawley and Paul Gosar. Dilanian:

The new National Terrorism Advisory System bulletin, released Wednesday afternoon, replaces an existing bulletin published in August, which said "ethnically motivated violent extremists and anti-government/anti-authority violent extremists will remain a national threat priority for the United States."

..."[T]hreats include those posed by individuals and small groups engaged in violence, including domestic violent extremists and those inspired or motivated by foreign terrorists and other malign foreign influences. These actors continue to exploit online forums to influence and spread violent extremist narratives and promote violent activity."

The ongoing pandemic continues to be a spark for violent rhetoric, DHS found, especially by those angered by mask and vaccine mandates and restrictions on normal activity.

If a new Covid-19 variant emerges and new restrictions are imposed, "anti-government violent extremists could potentially use the new restrictions as a rationale to target government or public health facilities."

Foreign intelligence services [Trumps' Russian allies], foreign terrorist organizations and domestic violent extremists "continue to introduce, amplify and disseminate narratives online calling for violence," the bulletin said.

They also "continue to derive inspiration and obtain operational guidance regarding the use of IEDs and small arms through the consumption of information shared in online forums."

"Extremists have called for attacks on elected officials, political representatives, government facilities, law enforcement, religious communities, commercial facilities and perceived ideological opponents."

John Cohen, DHS' head of counterterrorism and intelligence, told a House committee last week that "the period of threat that we are in today is one of the most complex, volatile and dynamic that I have experienced in my career."

Earlier today, reporting for the Washington Post, Professor Jeremy Best wrote that "Hitler was convicted of high treason for his leadership in the attempted coup, which left 20 people dead. Although a common punishment for treason was (and still is) death or a hefty prison sentence, Hitler received neither. The future Führer got... house arrest. The light sentence reflected the opinion of trial judge Georg Neithardt that Hitler had honorable motives even if they were misguided. Neithardt also dismissed the option of deporting Hitler back to his home country of Austria, saying the relevant laws could not be applied to a man 'who thinks and feels so German as Hitler' and shows such 'pure patriotic spirit and noble will.' The failure of the Weimar judiciary to adequately punish serious political crimes had a deep effect on support for the republic. Weak enforcement of laws encouraged right-wing opposition to liberal democracy and tacitly endorsed violence as an appropriate expression of political views. Meanwhile, voters-- especially communists opposed to the 'bourgeois republic'-- saw in the failures of the judiciary clear evidence that the republic and its systems of justice were broken. So voters on the left turned against the republic, too, frustrated by a legal system that seemed unwilling to stop the terrorist violence rising on the right. Under the Weimar Republic, right-wing traitors to the government were treated as patriots, and that spelled doom for the republic. In short, many German conservatives wanted to see the Weimar Republic fall-- and actively worked to undermine it. The question is whether political leaders in our own time want to see the American republic fall? Politicians are wrong to diminish or excuse violent attempts to change political outcomes. If they classify events like those of Jan. 6 as misguided expressions of patriotic loyalty, then they put the legitimacy of the American republic at risk. It happened once before in another place. We can only hope that Americans will see the peril before us and recognize 'overzealous' patriotism as no excuse for political violence."

Last month the DOJ put out a pathetic warning that "[T]he risk of future violence is fueled by a segment of the population that seems intent on lionizing the January 6 rioters and treating them as political prisoners, heroes, or martyrs instead of what they are: criminals, many of whom committed extremely serious crimes of violence, and all of whom attacked the democratic values which all of us should share... The threat of politically motivated violence is not gone. Political rallies, voting days, and certifications of votes are not everyday events, but they will happen again, and so too might the violence that our country witnessed on January 6, 2021." By "people," they mean Republican members of Congress like QAnon adherents Marjorie Traitor Greene (GA) and Lauren Boebert (CO), both of whom represent ed districts drawn to safely elect and reelect Republicans without any glimmer of competitiveness.

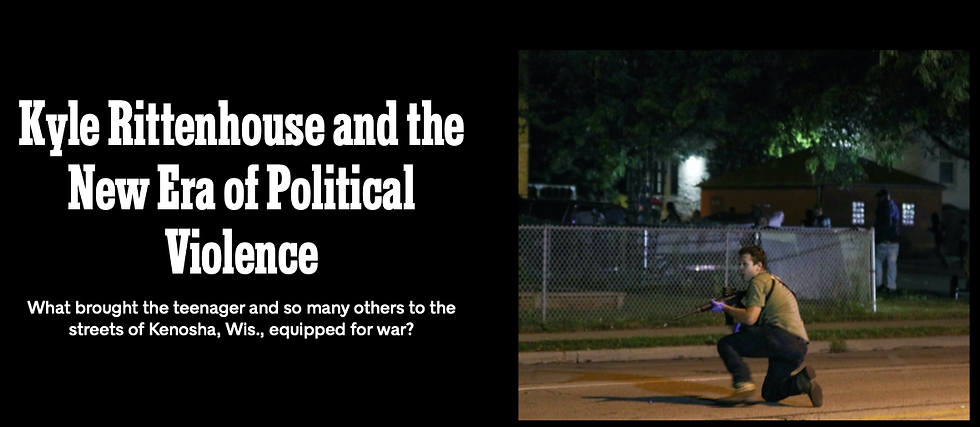

Many people have been watching the trial of neo-Nazi murderer Kyle Rittenhouse, presided over by a judge that could well be the head of the neo-Nazi cell that Rittenhouse is part of. Before the trial began, the NY Times reported that "the prosecutors and defense attorneys will take up the question that politicians and media personalities have spent the past year confidently answering: Who is he, and why did he do what he did? The rush to define him began immediately. After the shooting, Representative Ayanna Pressley, the Democratic congresswoman from Massachusetts, called him a 'white supremacist domestic terrorist' on Twitter and castigated news outlets for describing him as anything less. The right claimed him just as quickly as a singular hero. 'I would describe him as a Minuteman,' John Pierce, a lawyer who attached himself to Rittenhouse’s case, told a columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times. 'KYLE RITTENHOUSE FOR CONGRESS,' Anthony Sabatini, a [fascist] Republican state representative in Florida, tweeted. 'I want him as my president,' Ann Coulter tweeted. 'ALL THE BEST PEOPLE #StandWithKyle,' the right-wing commentator Michelle Malkin tweeted. 'It’s now or never... and, yes, it’s war.'"

Trump had labored for several years to make a national boogeyman out of antifa, the left-wing anti-authoritarian movement, directing law-enforcement resources toward it that had been dedicated to investigating right-wing extremism and threatening to designate it a terrorist group, despite his F.B.I. director’s belief that it was really “more of an ideology than an organization.” In the antifa heartland of Portland, Ore., the upheavals following George Floyd’s death brought members of the movement together with Black Lives Matter activists in clashes with the police that would continue for months. In other cities, the streets were filled with white demonstrators who at least looked like antifa. These developments offered an end run around the messy racial optics of a law-and-order campaign that directly targeted Black protesters.

In a speech on June 1 in the Rose Garden, Trump announced that he was urging governors to deploy federal law-enforcement officers and National Guard troops to quell the chaos in Portland and elsewhere. (He would later go further, sending waves of federal law-enforcement officers over the protestations of local leaders.) He dutifully denounced the “brutal death of George Floyd” but also the “acts of domestic terror” that followed his killing, never mentioning Black Lives Matter and instead blaming “antifa and others who were leading instigators of this violence.” The next day, Fox News published a story claiming, according to a single anonymous “government intelligence source,” that antifa had a coordinated national plan to bring chaos and destruction to the suburbs. “Local and state authorities have to get a grip on this,” the source said, “because if it moves to the suburbs, more people will die.”

It was inevitable in this political climate that confronting demonstrators would become a path to right-wing celebrity. On June 28, Mark and Patricia McCloskey, a wealthy couple in St. Louis, were captured in a much-circulated video aiming guns at protesters marching past their home; two months later, the night before the Rittenhouse shootings, they addressed the Republican National Convention. “What you saw happen to us could just as easily happen to any of you who are watching from quiet neighborhoods around our country,” Patricia McCloskey said. “Your family will not be safe in the radical Democrats’ America.”

The month after George Floyd’s death was full of examples of people following this idea to its logical conclusion. In towns across Idaho, groups of armed men materialized on the street in response to unfounded Facebook rumors about incipient antifa activity. A group of men with bats and golf clubs faced down Black Lives Matter demonstrators in the street in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood, some shouting racial slurs. And on June 15, a group of armed men surrounded protesters in Albuquerque, N.M., trying to tear down a statue of New Mexico’s 16th-century colonial governor, the conquistador Juan de Oñate, who slaughtered hundreds of Pueblo people during his rule. Amid rising tension, one of the men, Steven Ray Baca Jr., pepper-sprayed members of the crowd. As one man reportedly swung a skateboard at him, Baca fired his handgun four times, wounding the man.

Baca (who is currently awaiting trial), the son of a sheriff’s deputy and a recent candidate for City Council, posted a MAGA-hatted selfie from a Trump rally the previous September. He was defended at the protest by the New Mexico Civil Guard, which formed a year before in opposition to gun laws proposed by the state’s Democratic governor and became a regular counterpresence at protests. Its leader, Brice Smith, told a local reporter that they hoped to be “a visual deterrent” to would-be statue topplers: “Our goal there was to make sure violence didn’t spill out from the area of the statue.” Where American militias once defined themselves principally in opposition to the federal government, groups like the New Mexico Civil Guard now often defined themselves explicitly or implicitly in relation to Democratic governments, national or local-- either in opposition to them or their policies or as a compensation for what they saw as their obvious failures at law enforcement. And they increasingly defined their mission as protecting against the excesses of the new wave of racial-justice demonstrations.

...[Tucker] Carlson’s take on the events in Kenosha was in line with what others in local conservative media were saying. “I’m tired of seeing these subhumans be allowed to destroy property,” David Clarke told Vicki McKenna on her radio show that afternoon. “I’m tired of seeing officers injured with tepid response in reply.” McKenna agreed. Recurring themes of that broadcast, as she talked with Clarke and other guests, were what McKenna contended was the complicity of Democratic officials in the destruction, and its highly organized nature. “It doesn’t take a conspiracy theorist to see it,” McKenna said. “All you’ve got to do is watch this video and ask yourself, ‘Well, what are all those white kids doing there?’” She continued, “And what are we going to do about it?”

...[D]onations were pouring in for Rittenhouse’s defense-- several million dollars, eventually-- and two high-profile right-wing civil attorneys, L. Lin Wood and John Pierce, had announced that they would represent him. One of the two Wisconsin defense attorneys they hired was Jessa Nicholson Goetz, a Madison lawyer who also happened to be representing Kerida O’Reilly, one of the racial-justice demonstrators charged with assaulting Tim Carpenter at the State Capitol two months earlier (O’Reilly was acquitted in October). To Goetz, the two clients, who fell at opposite poles of the street politics of 2020, were not so dissimilar. Both had placed themselves in situations where political elites-- local and national, Republican and Democratic-- had abdicated their basic obligation to discourage their partisans from burning down a police station or playing soldier. “The reason all this is happening is we have a government that is unwilling to govern,” Goetz told me. “We’re too busy hating each other-- and our kids are getting killed.”

This was not Wood’s and Pierce’s view of the case. On social media and in TV interviews, they cast Rittenhouse in mythic terms. Pierce announced, on Tucker Carlson’s show, that the defense team would be invoking Title 10, Section 246 of the U.S. Code: the clause defining the classes of militias. On Twitter, he compared the shots Rittenhouse fired to the start of the Revolutionary War in the battles of Lexington and Concord. According to Chris Van Wagner, Goetz’s co-counsel, Wood-- who also represented the McCloskeys-- spoke of Rittenhouse in terms of biblical prophecy. “He said: ‘God always sends boys to get his message across. He sent Christ as a boy,’” Van Wagner told me. “ ‘He sent Kyle Rittenhouse to re-establish the right to self-defense.’”

Goetz and Van Wagner left the defense in a matter of days. Within a few months, Wood would be gone, too, subsuming himself instead in the election-fraud lawsuits filed on behalf of Trump. (Wood did not respond to requests for comment.) By early this year, Pierce was out as well, fired by Rittenhouse amid disputes over the management of the funds that had been raised; he is now representing multiple defendants in the federal cases stemming from the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. (“It remains my sincere hope that Kyle is able to receive the justice he deserves and that the entire Rittenhouse family can soon put this tragic situation behind them,” Pierce said in an email.) Rittenhouse was adopted as an informal mascot by the far-right group the Proud Boys; he was photographed surrounded by local Proud Boys in a bar after his release on bond, and The New Yorker reported that he and his mother visited the group’s national leader in Florida in January. But as the year went on, Rittenhouse’s loudest champions in more mainstream conservative media and politics mentioned him less and less.

The day after the shootings, a deployment of officers from multiple federal agencies arrived in Kenosha. “Since the National Guard moved into Kenosha, Wisconsin, two days ago, there has been NO FURTHER VIOLENCE, not even a small problem,” Trump tweeted later that week, shortly before traveling to Kenosha to tour the wreckage. Asked by reporters about Rittenhouse in a news conference several days after the shootings, Trump was supportive: “You saw the same tape as I saw, and he was trying to get away from them-- I guess it looks like, and he fell, and then they very violently attacked him.” But he did not mention him once in his remarks in Kenosha.

This was the limbo into which Rittenhouse fell in the Republican imagination over the year after the shooting. He still received the occasional shout-out-- the tweets of support from Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, for instance, in the weeks before his trial. But now he was more often the subject of uncomfortable silences. Shortly after the shootings, Erin Decker, the county party chair and county supervisor, told the hosts of “Fox and Friends” that “talking to people around the area, I would say about 80 percent of the people support what Kyle did.” In June, I asked Decker if she thought that was still true. “Most definitely,” she said. “They’re just quiet because they know that people will attack them, and the news media will go after them also for defending what he did.”

Rittenhouse’s current lawyers-- led by Mark Richards, a criminal defense attorney in Racine-- have crafted a conventional self-defense case that is unlikely to mention the battles of Lexington and Concord or Wood’s prophecies. Many people initially suspected that Rittenhouse was drawn to Kenosha by Kevin Mathewson’s Facebook post and the many bloody-minded comment threads trailing behind it. But a forensic audit of Rittenhouse’s phone conducted by the local police showed no engagement with the post or any of the other calls to arms in Kenosha. Rittenhouse was already in Kenosha by the time Mathewson posted it, having arrived the night before with Dominick Black, an 18-year-old friend who bought the gun Rittenhouse would carry the next day and, according to police reports, met the owners of the car lot he and Rittenhouse would end up defending.

As for Rittenhouse’s politics, his since-deleted social media accounts suggested they had been conventional enough: He attended a Trump rally in February, and he had an interest in guns and a total adoration of the police. His posts were scattered with images of the Thin Blue Line: a black-and-white American flag with a single blue stripe, embodying the tribal vision of law enforcement as the only thing keeping anarchy from overrunning society. This was the basis of his support for Trump, Dave Hancock insisted to me: “He liked Trump,” he said, “because Trump liked the police.”

After an early jailhouse phone interview with the Washington Post, Richards, Rittenhouse’s criminal defense lawyer, generally kept his client clear of reporters. Since then, Hancock, a former Navy SEAL who runs a private security firm, had become a de facto spokesman for the Rittenhouse family. In our conversations, he often seemed to be previewing Rittenhouse’s lawyers’ defense: Rittenhouse’s decision to go to Kenosha with a gun was an act of teenage knuckleheadedness derived not from political extremism but from a misguided desire to serve the community, and he acted understandably and legally, if regrettably, in undeniably chaotic circumstances. This argument challenged the claims of Rittenhouse’s detractors, of course, but it also more subtly challenged the more strident claims of his supporters and of other paramilitaries who were there that night, who continued to insist that their actions were a legitimate exercise of civic duty. As one man who guarded the car lot with Rittenhouse that night insisted on McKenna’s show three days later, “We were, like I said, there to help.”

The paramilitaries did not seem to understand what lay beneath the surface of that statement-- how much privilege was required to declare yourself the defender of someone else’s neighborhood simply because you owned a gun. On Aug. 24, Koerri Washington captured on video an exchange on the street between three heavily armed young white men and a Black man who was loudly lamenting the Blake shooting, in which they tried unsuccessfully to persuade him that they were on the same side. One of the group, his face half-obscured by a yellow bandanna, approached Washington. “Just ’cause I don’t live in this neighborhood,” he asked, “am I that out of line?”

Watching the video, I thought I recognized the man. He had attended a gun rights rally the month before in Virginia, where he had been photographed with members of the Boogaloo: a nebulous far-right movement that gained traction online in 2019, espousing a wild-eyed anarcho-libertarianism that often involved calls to-- and occasional acts of-- violence against law enforcement. Rittenhouse had appeared briefly alongside the man in the yellow bandanna and several other Boogaloo bois, as they call themselves, in a scrum of paramilitaries gathered at a gas station the following night, an hour or so before the shootings. During one of our phone calls in August, I texted Hancock a photo of the man.

“Hey, Kyle, did you talk to this guy?” Hancock called out. He was at home in Reno, Nev., where Rittenhouse had gone to stay with him before the trial. Rittenhouse had been sitting in the room, I suddenly realized, as we were talking.

“I remember him saying, ‘I don’t give a [expletive], burn down the police station,’” Rittenhouse told Hancock.

He said it offhandedly, but it was striking: The one overwhelming theme of Rittenhouse’s since-deleted social media presence, and the videos of his post-arrest interviews with detectives, was that Kyle Rittenhouse loved the police-- had wanted to be a cop or an E.M.T. since he was a little boy, had joined the Police Explorers (a youth law-enforcement program) as an adolescent, had seen what he was doing in Kenosha that night as some form of emergency service. And yet in the last minutes before he ended two lives and changed his own forever, he found himself in the street alongside members of a movement that had killed two law-enforcement officers and professed a desire to bring down the state.

All the Thin Blue Line and the Boogaloo had in common was what they stood against: the forces they believed were gathering on the left to erase the idea of America, however conventionally or radically you defined it. In Kenosha, those forces were some confederation of antifa, Black Lives Matter and Democratic officials, depending on whom you asked. But they did not have to be. In the months after Kenosha, similar armed coalitions showed up at “Stop the Steal” rallies protesting imagined threats to the election at several state Capitols. “Kenosha was a harbinger of that,” said Andy Carvin, managing editor of the Digital Forensic Research Lab at the Atlantic Council think tank, where he tracked the online mobilization efforts leading up to the night of the Rittenhouse shootings.

All of these episodes looked, in retrospect, like steppingstones on the way to the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol, where a coalition of standard-issue Trump voters, QAnon true believers and militiamen united in an attempt to blow up American democracy in order to save the country from their perceived enemies. We had entered a new era in which there would always be an enemy and someone ready to meet them. It was clear, by then, that what happened in Kenosha was about something much bigger than the buildings that burned there. It did not really matter if dozens of buildings were burning or one was. It did not really matter if buildings were burning at all.

societal chaos not all that dissimilar to the formation of the brownshirts in germany. They too thought of themselves as patriots, but more to the german race than the Weimar republic, which most of them truly loathed. And in service to their race, they sought to destroy the republic so they could destroy the political relevance of communists, social democrats and other "others". The Great Depression was their "oppurtunity" and their choice of jews as scapegoats for everyone's abject misery became the perfect storm.

And, as in germany, those tasked with keeping the republic (enforcing rule of law and the founding document as well as societal norms) refused to do so for plenty long enough to allow the nascent evil…