What Is a State? Why Do We Live in Them?

- Thomas Neuburger

- Sep 9, 2025

- 6 min read

By Thomas Neuburger

“The state is an inherently coercive social system for exploiting and immiserating the many to benefit the few. States differ in this quality only by degree.” —Yours truly

This starts our look at James C. Scott’s brilliant examination of the origin of states, a book named Against the Grain. We peeked at two of Scott’s insights in this earlier post.

As usual, this won’t be a book review as such, but a selection of insights to help us answer the primary question inspired by David Graeber:

How did we get stuck in these destructive, exploitive structures when so many other ways to live were available?

My original thought was that our warlike Western way had its source in the conquering proto-Indo-European people who worshiped a “sky father” god — Dyḗus ph₂tḗr, Deus phter, Zeus or Jupiter — and fought their way out of the steppes, sweeping before them settled neolithic farmers and replacing the female gods who gave them grain.

I still think that’s plausible, as you’ll see later in this series. But first, we have to consider the nature of states. There’s a 4000-year gap between start of sedentism and proto-agriculture — life in one place, life with stable food — and the emergence of the oppressor we’ve come to call “the state.” (Why “the oppressor”? Read on.)

The Rise of Sedentism in Selected Places

Sedentism could only begin in certain locations — basically, nutrition-rich wetlands and deltas. He discusses what he calls the “standard narrative” — the “sequence of progress from hunting and gathering to nomadism to agriculture (and from band to village to town to city).” Then says this (emphasis mine):

It turns out that the greater part of what we might call the standard narrative has had to be abandoned once confronted with accumulating archaeological evidence. Contrary to earlier assumptions, hunters and gatherers—even today in the marginal refugia they inhabit—are nothing like the famished, one-day-away-from-starvation desperados of folklore. Hunters and gathers have, in fact, never looked so good—in terms of their diet, their health, and their leisure. Agriculturalists, on the contrary, have never looked so bad—in terms of their diet, their health, and their leisure.[6] The current fad of “Paleolithic” diets reflects the seepage of this archaeological knowledge into the popular culture. The shift from hunting and foraging to agriculture—a shift that was slow, halting, reversible, and sometimes incomplete—carried at least as many costs as benefits. Thus while the planting of crops has seemed, in the standard narrative, a crucial step toward a utopian present, it cannot have looked that way to those who first experienced it: a fact some scholars see reflected in the biblical story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The wounds the standard narrative has suffered at the hands of recent research are, I believe, life threatening. For example, it has been assumed that fixed residence—sedentism—was a consequence of crop-field agriculture. Crops allowed populations to concentrate and settle, providing a necessary condition for state formation. Inconveniently for the narrative, sedentism is actually quite common in ecologically rich and varied, preagricultural settings—especially wetlands bordering the seasonal migration routes of fish, birds, and larger game. There, in ancient southern Mesopotamia (Greek for “between the rivers”), one encounters sedentary populations, even towns, of up to five thousand inhabitants with little or no agriculture. The opposite anomaly is also encountered: crop planting associated with mobility and dispersal except for a brief harvest period. This last paradox alerts us again to the fact that the implicit assumption of the standard narrative—namely that people couldn’t wait to abandon mobility altogether and “settle down”—may also be mistaken.

And about domestication as a decisive step in the creation of civilization and therefore states, Scott says this:

Perhaps most troubling of all, the civilizational act at the center of the entire narrative: domestication turns out to be stubbornly elusive. Hominids have, after all, been shaping the plant world—largely with fire—since before Homo sapiens. What counts as the Rubicon of domestication? Is it tending wild plants, weeding them, moving them to a new spot, broadcasting a handful of seeds on rich silt, depositing a seed or two in a depression made with a dibble stick, or ploughing? There appears to be no “aha!” or “Edison light bulb” moment. There are, even today, large stands of wild wheat in Anatolia from which, as Jack Harlan famously showed, one could gather enough grain with a flint sickle in three weeks to feed a family for a year. Long before the deliberate planting of seeds in ploughed fields, foragers had developed all the harvest tools, winnowing baskets, grindstones, and mortars and pestles to process wild grains and pulses.[7] For the layman, dropping seeds in a prepared trench or hole seems decisive. Does discarding the stones of an edible fruit into a patch of waste vegetable compost near one’s camp, knowing that many will sprout and thrive, count?

So free your mind of the counter-factual assumption, that there’s a straight and necessary line from hunter-gatherer uncertainty to cozy state life. The line’s neither straight nor necessary, and the state was coercive, not cozy.

What places were wet and rich enough to support hunter-gatherer sedentism? (This is my term for a hunter-gatherer life with no moving around, as opposed to state-controlled sedentism — my term again — where food, and therefore, people are centrally controlled.)

Scott lists those places; they’re the usual suspects: the southern Mesopotamian alluvium (the silted area of the Tigris-Euphrates delta), the area around Jericho, the Levant, the Nile delta and Indus valley, northern China, and so on. In sum, not that many, and crucially, not all of these places grew states, which has special requirements.

Timeline of State Formation in Mesopotamia

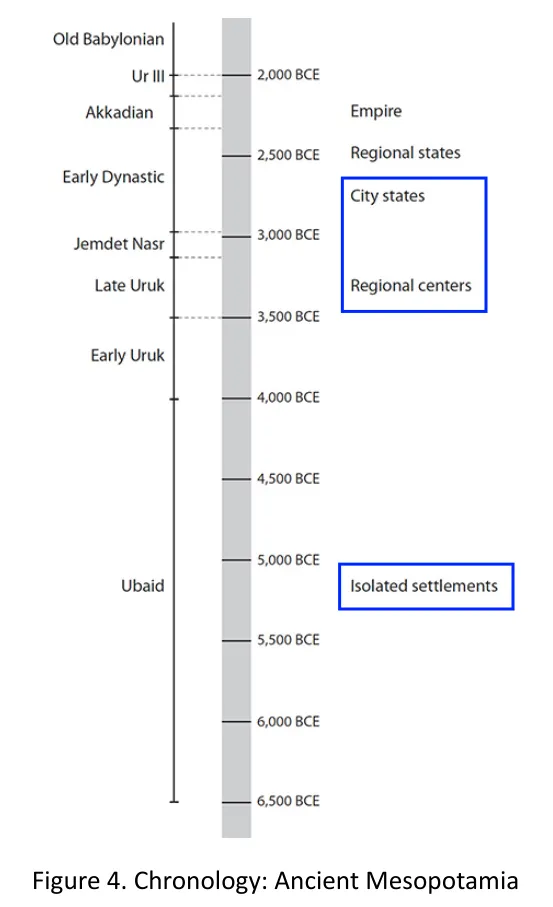

I’ll close with two points. One is a timeline of state formation in Mesopotamia to support the idea of the long pre-state gap between the start of sedentary life and the creation of states.

The following is adapted from Scott’s Figure 4 (blue boxes mine).

The Late Uruk period is the time of first state formation. Settlements — hunter-gatherer sedentism — preceded that by millennia with no states in sight.

Topics Discussed in This Series

The book’s argument proceeds quite logically, so this series will be following that. Its chapters are these:

1. The Domestication of Fire, Plants, Animals, and … Us

Before we could be made the object of state making, it was necessary that we gather—or be gathered—in substantial numbers with a reasonable expectation of not immediately starving.

2. Landscaping the World: The Domus Complex

This chapter looks at the length of the human project: landscaping the world. This process starts with the domestication of fire by Homo erectus — and fire’s domestication of us.

3. Zoonoses: A Perfect Epidemiological Storm

The burdens of life for nonelites in the earliest states … were considerable. The first, as noted above, was drudgery. … A second great and unanticipated burden of agriculture was the direct epidemiological effect of concentration … Diseases with which we are now familiar—measles, mumps, diphtheria, and other community acquired infections—appeared for the first time in the early states.

4. Agro-ecology of the Early State

It is surely striking that virtually all classical states were based on grain, including millets. … My guess is that only grains are best suited to concentrated production, tax assessment, appropriation, cadastral surveys, storage, and rationing.

5. Population Control: Bondage and war

If the formation of the earliest states were shown to be largely a coercive enterprise, the vision of the state, one dear to the heart of such social-contract theorists as Hobbes and Locke, as a magnet of civil peace, social order, and freedom from fear, drawing people in by its charisma, would have to be reexamined.

6. Fragility of the Early State: Collapse as Disassembly

The agro-ecology favorable to state making is relatively stationary, while the states that occasionally appear in these locations blink on and off like erratic traffic lights.

7. The Golden Age of the Barbarians

Barbarians are not essentially a cultural category; they are a political category to designate populations not (yet?) administered by the state. The line on the frontier where the barbarians begin is that line where taxes and grain end.

I hope each of these topics will draw you back. Yet as interesting in themselves as they are, we’re not going to lose sight of our goal, which is to discover:

What is a state?

What are the alternatives to states?

Why are we stuck in states?

How to get free of them?

One thought for free: Like it or not, this century will see the end of state formation and the forced return to alternatives. Some alive will see this; all of their children will.

Please join us as we continue this examination. I’m looking forward to it.

Comments