Are You An Activist? Do You Have A Dilemma? What Are We Going To Do About The Genocide In Gaza?

- Howie Klein

- Feb 12, 2024

- 8 min read

Robb Willer is a much admired Stanford sociologist who studies, among other things, the effectiveness of activists’ tactics. I heard him on NPR talking about it yesterday. It didn’t surprise me when he said that when passionate activists use violence or aggressive disruption to protest their cause, they tend to turn off more people than they recruit to that cause— and it’s not even close. I wish I could have talked to him about how to protest the urgency of something as existential as genocide.

In a paper he wrote while Trump was still in the White House, he and his research partner, Matthew Feinberg, didn’t exactly answer that but wrote about a moral empathy gap: “The political landscape in the US and many other countries is characterized by policy impasses and animosity between rival political groups. Research finds that these divisions are fueled in part by disparate moral concerns and convictions that undermine communication and understanding between liberals and conservatives. This ‘moral empathy gap’ is particularly evident in the moral underpinnings of the political arguments members of each side employ when trying to persuade one another. Both liberals and conservatives typically craft arguments based on their own moral convictions rather than the convictions of the people they target for persuasion. As a result, these moral arguments tend to be unpersuasive, even offensive, to their recipients. The technique of moral reframing— whereby a position an individual would not normally support is framed in a way that is consistent with that individual's moral values— can be an effective means for political communication and persuasion. Over the last decade, studies of moral reframing have shown its effectiveness across a wide range of polarized topics, including views of economic inequality, environmental protection, same‐sex marriage, and major party candidates for the US presidency. In this article, we review the moral reframing literature, examining potential mediators and moderators of the effect, and discuss important questions that remain unanswered about this phenomenon.

Four years earlier, Willer and Feinberg had already conducted 6 studies with over 1,300 participants. Willer told the Stanford News that they found “the most effective arguments are ones in which you find a new way to connect a political position to your target audience’s moral values… Moral reframing is not intuitive to people. When asked to make moral political arguments, people tend to make the ones they believe in and not that of an opposing audience— but the research finds this type of argument unpersuasive.” Feiberg added that “Our natural tendency is to make political arguments in terms of our own morality. But the most effective arguments are based on the values of whomever you are trying to persuade.”

Willer laid out this part of their research (more reframing) well as part of a TEDTalk he did in 2017. Watch:

He didn’t get into the activist’s dilemma but I stumbled onto a paper he, Feinberg and Chloe Kovacheff had published in November 2020 in Stanford’s Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, The Activist’s Dilemma: Extreme Protest Actions Reduce Popular Support for Social Movements. Their goal had been to “test the claim that extreme protest actions— protest behaviors perceived to be harmful to others, highly disruptive, or both— typically reduce support for social movements.” They found that the result of their experiments— across a variety of movements (e.g., animal rights, anti-Trump, anti-abortion) and extreme protest actions (e.g., blocking highways, vandalizing property)— validated the claim. “Taken together with prior research showing that extreme protest actions can be effective for applying pressure to institutions and raising awareness of movements, these findings suggest an activist’s dilemma, in which the same protest actions that may offer certain benefits are also likely to undermine popular support for social movements.”

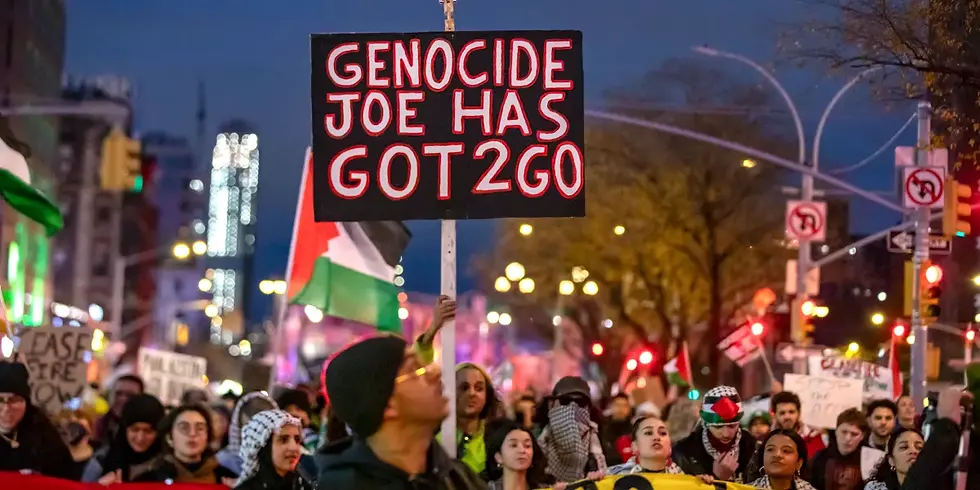

Nadra Nittle wrote about this work and interviewed Willer for Stanford Business soon after the J-6 insurrection. Since I’ve been thinking a lot about the genocide going on in Gaza right now, I want to take a brief detour from Stanford before getting back to Willer. I hope you agree with me that there’s no rational or morally justifiable defense for genocide. If you disagree, you’re probably on the wrong blog. Genocide is one of the most egregious and heinous crimes against humanity, involving the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of a targeted group based on their ethnicity, nationality religion, or other identifying characteristics (LGBTQ, handicapped…) It represents a flagrant violation of human rights, dignity, and the most basic principles of morality and decency, right? And it inflicts immeasurable suffering, loss, and trauma on its victims and their communities, and it leaves lasting scars on societies and future generations— the way it did during the Holocaust in the 1940s— currently much-denied in MAGA world— and the way it is now in Gaza. And it’s pretty much universally condemned by international law, ethical principles, and the collective conscience of humanity. Efforts to rationalize or justify genocide— or be complicit in it— are not only morally bankrupt but also dangerous, as they can perpetuate hatred, bigotry, and violence. It is incumbent upon individuals, communities, and nations to unequivocally reject and condemn genocide in all its forms and to work tirelessly to prevent and combat such atrocities wherever they occur. There is no sane or legitimate defense for genocide. It’s an abhorrent crime that stands as a stark reminder of humanity's capacity for cruelty and injustice, and it must be met with unwavering condemnation, accountability, and action to ensure that such atrocities are never repeated.

I was driven nearly crazy in college while the U.S. was destroying Vietnam. As a teenager, I was certain that refusing to participate in or support the genocidal actions of the regimes is a moral imperative. This required civil disobedience, noncooperation. I never got to sabotage to undermine the perpetrators' ability to carry out their crimes, although later in life I became, close with the mother of a friend who, as a young girl, blew up a Nazi troop train in Holland. I moved abroad for over 6 years. Advise: If you’re fighting genocide aggressively and staying in the country puts you at risk of harm, it may be necessary to consider escaping to a safer location.

We’ve all thought of this is our lives: Would it have been ethical to take action against individuals like Hitler, Eichmann, and other perpetrators of genocide during the Holocaust? Spoiler: Yes. The atrocities committed in extermination camps such as Treblinka, Majdanek, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chełmno, Belzec, and Sobibor were among the most horrific crimes in human history, and any means of resisting or opposing such genocide would have been morally justifiable. Individuals who were aware of the atrocities being perpetrated by the Nazi regime had a moral obligation to speak out against them and take whatever action they could to resist or prevent further harm. This could have included acts of defiance, sabotage, providing aid to victims, hiding or sheltering persecuted individuals or participating in organized resistance movements. Acts of courage and moral integrity, whether large or small, play a crucial role in resisting tyranny and upholding human dignity in the face of unspeakable evil. While the risks and consequences of taking action against the Nazi regime were severe, standing idly by and allowing genocide to occur would have been a betrayal of basic human decency and a failure to uphold the most fundamental principles of morality. In such extraordinary circumstances, the imperative to resist injustice and protect innocent lives outweighs personal safety and self-interest.

OK, back to Willer’s findings about the activists’ dilemma. Nittle wrote that “How the public perceives protest behaviors largely stems from a common sense of right and wrong, and extreme actions such as threats of violence, major disruptions or inflammatory rhetoric tend to be viewed as immoral. Once observers of a movement form this perception, they’re unlikely to feel the compassion needed to identify with a cause, and activists who behave in ways thought to violate the rights of others run the risk of permanently alienating the public. When protest actions are deemed immoral, they have the potential to prompt observers to reject a movement’s entire platform. For example, the researchers contend that activists who block highway traffic to raise awareness about the environment might lose public support for the movement— and provoke the public to care less about conservation efforts generally. That said, if the cause has long been the subject of moral debate, an extreme protest action is unlikely to change public opinion.”

So I guess Hilda and her two brothers blowing up the Nazi troop train would have been judged a mistake. Or is there a place where you can draw a line? After the war, the Dutch government gave her an award and a pension for life. In fact, Nittle wrote that “in an experiment involving anti-Trump protesters, with politically liberal study participants reporting a drop in support for demonstrators who caused a traffic jam by blocking carloads of Trump supporters from reaching one of his campaign events. ‘We were very surprised by how consistent these effects were across different groups of Americans,’ Willer says. ‘You would think that people would show a great deal of deference to activist groups that are representing their political or demographic group and not be negatively influenced by their extreme tactics, but that’s not what we found. People still prefer those groups not to use extreme tactics.’ In some circumstances, extreme protest behaviors, such as activists using force to topple a totalitarian regime, might foster public support. The research findings also suggest that activists engaging in extreme protest should make efforts to explain the rationale behind that decision. For instance, holding up signs that communicate the urgency of their cause could offset the idea that they’re blocking traffic because they’re ‘immoral.’”

On Jan. 6, protesters stormed the U.S. Capitol, seemingly convinced that their decision to trespass on federal property and rifle through the belongings of government officials presented them as brave patriots fighting against a corrupt political system. But, as Willer points out, the public perceived them very differently.

“I think this research captures well the storming of the Capitol,” he says. “This was an act of violent and disruptive protest that certainly grabbed headlines but was met with overwhelming condemnation. While the riot may be effective for emboldening the base of activists already involved or drawing some very fringe individuals to join the cause, it was utterly ineffective in persuading the mass public to embrace the rioters’ grievances.”

Afterward, some Republicans made a concerted effort to distance themselves from these protesters, who claimed that the 2020 presidential race had been stolen from Trump. To distinguish themselves from the rioters, a group of Republican lawmakers changed their position on the integrity of the presidential election and voted to certify the results.

So, why didn’t the Capitol protesters predict what the response to their siege would be? Highly invested in their movements, activists are prone to assuming that the general public feels nearly as strongly about a particular cause as they do— or they have difficulty considering the viewpoint of people who don’t know or care about the issue. But the researchers assert that their findings strongly suggest that resolving the activist’s dilemma could be the key to movement success.

To avoid alienating the public, activists might rely on moderate protest tactics. Alternatively, if a movement has just started to take off, activists could initially use extreme behaviors to draw attention to their cause and then revert back to modest methods to maintain public support. Still, the researchers acknowledge that there certainly may be exceptions to the rule. They point out that the American, Cuban, Russian, and French revolutions all won broad popular support, despite the fact that the individuals who spearheaded these movements used extreme actions to resist.

“The truth is that this space of how social movements succeed or fail in pushing their agenda in society is an extremely complex dynamic that we don’t fully understand,” Willer says. “To give a complete theory of this, you’d need to account for these kinds of exceptions.”

In a contemporary democracy such as the United States, where the civil rights movement remains influential, nonviolent methods of protest are arguably received the best. But nonviolent doesn’t mean non-extreme. The civil rights activists of the 1960s marched on roads and bridges and disobeyed Jim Crow laws until the police arrived to arrest them. In their day, they were highly disruptive but still managed to win popular support. A modern movement could do the same.

“You really need to think about what activists are protesting against,” Willer says. “If they’re protesting against a repressive dictatorship, for example, they might not really lose that moral standing because they’re seen as striking back against a very immoral agent.”

Having lived through the Viet Nam era with all the activism which seemed to meld into the era of women's rights activism, I am dumbfounded by the absolute dearth of activism today. Dobbs created some, but not enough. But the past few decades of burgeoning hate and violence that have all been normalized politically and socially have resulted in almost nothing.

Do we not care?

again, censoring truth won't change it. maybe if you actually tried to, you know, MAKE this a better shithole instead of promoting MOS with your beloved democraps...